On Blemishes

The ugliness of our bodies signals something better to come.

by Lara Ryd

A couple of weeks ago, blisters started forming on my toddler’s body. Blisters everywhere. Blisters, it seemed, on top of blisters. They started out as little red spots, which soon started to come loose from the skin. Thankfully, I’d had warning that he’d been exposed to hand, foot, and mouth, so these symptoms didn’t come as a surprise. Even so, it was distressing to see his little hands, feet, and legs covered with the itchy, scaly rash. There were even sores inside his mouth.

That same week I’d come down with a bad cold that made it impossible to breathe through my nose. My ears were clogged, and my nose had become chapped from the never-ending stream of tissues. About half-way through the week, I found myself getting frustrated with all this sickness—not just because of the inconvenience, but because of the ugliness. The thought kept occurring to me that the human body is gross. Even when the body is working properly and fighting off threatening viruses, the side effects are vile: mucus, rashes, vomit, diarrhea. Then there’s the stuff that many of us just learn to live and deal with as a normal part of life: hemorrhoids, foot fungus, ingrown hairs, canker sores, ear wax, acne, IBS, eczema, gas. Gross.

We usually keep these kinds of physical conditions hidden. No one wants to walk into an art museum and see sculptures celebrating these features of the human body. We avoid discussing them at the dinner table. You’ll never see them as major plot points in movies, and if you do, you likely won’t see them shown on screen. We save the truly disgusting physical conditions for historical dramas, when there’s a sense of respect and sobriety holding us to image. The truth is that we just don’t like to look at bodily blemishes. They’re ugly and offensive—and sometimes even sickening—so we avert our gaze.

When we ourselves are afflicted with physical blemishes, they often are a source of shame. I still remember the shame I felt when I got my first menstrual cycle as a 12-year-old. It’s not because I was unaware that this was a sign of a healthy, functioning female body—it was because I felt gross. I can remember another year when I refused to attend an Easter service because my skin was (in my mind) in such terrible shape. While this shame often appears during adolescence, when our bodies start changing and we start noticing, it doesn’t necessarily disappear once our hormones have balanced out. I wasn’t expecting physical shame to carry over into my marriage, but it did, and for good reason: I no longer could keep my physical blemishes hidden from my husband. It often feels impossible to share yourself with another person when you feel unlovely.

⧫⧫⧫

When we cannot hide our blemishes, they tend to isolate us. Such was the case for many of the men and women whom Jesus encountered during his ministry: the lepers, the blind, and the paralytic, the woman with the constant discharge of blood, the deaf mute, the man with the withered hand. Their defects made them outcasts, not only because some people saw physical maladies as consequences for sin (John 9:2), but also because the Mosaic law rendered those with certain kinds of blemishes ritually unclean. Lepers could not touch other people because such physical contact would contaminate others. Similarly, women with menstrual discharges were considered ritually unclean under the same law. God had given these laws to declare his perfection and provide a picture of His standards of holiness. Nothing that was blemished could approach the tabernacle, and the sacrificial lamb itself had to be “without blemish” (Ex. 12:5).

But these ceremonial laws were a sign, and “a shadow of the good things to come” (Heb 10:1). When Jesus began his ministry, the “true form” which the author of Hebrews speaks of began to unfold: he touched those with blemishes. In the most palpable, conspicuous ways. He makes mud with his own saliva and anoints the blind man’s eyes (John 9:6). He takes the hand of a dead girl and helps her onto her feet (Luke 8:54). He touches the leper and commands his body to be clean (Matt. 8:3). And though the desperate touch of the bleeding woman is hidden, Jesus feels it and blesses it (Luke 8:46-48).

Time and time again, Jesus, the lamb without blemish, touches those with blemishes and makes them clean. In doing so, he fulfills Isaiah 53:2-5:

"For he grew up before him like a young plant,

and like a root out of dry ground;

he had no form or majesty that we should look at him,

and no beauty that we should desire him.

He was despised and rejected by men,

a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief;

and as one from whom men hide their faces

he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Surely he has borne our griefs

and carried our sorrows,

yet we esteemed him stricken,

smitten by God, and afflicted.

But he was pierced for our transgressions;

he was crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that brought us peace,

and with his wounds we are healed."

Though often translated as “griefs,” the Hebrew word חֳלִי also means “illnesses,” such that Matthew translates this verse into Greek as: “He took our illnesses and bore our diseases” (Matt. 8:17).

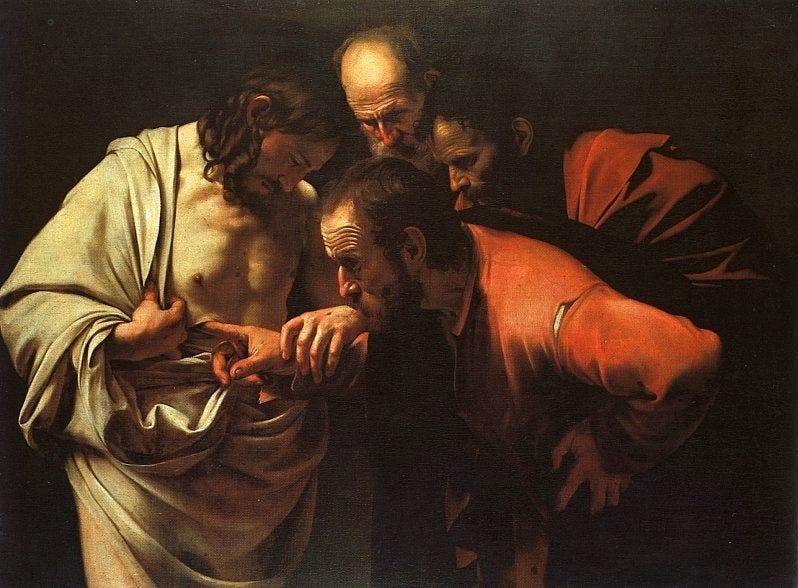

We might put it another way: he bore our blemishes. Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross physically wounded him—and these wounds remained even in his resurrected body. His blemishes were made glorious in the resurrection, a permanent sign of his work of atonement. In bearing our blemishes, Christ made a way for us to approach—and to always be with—a holy and perfect God. His works of bodily healing were but a taste of the true healing work accomplished on the cross.

Therefore, brothers, since we have confidence to enter the holy places by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain, that is, through his flesh, and since we have a great priest over the house of God, let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, with our hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water. (Hebrews 10:19-22)

The blemishes our bodies bear will increase as we get older, and this, too, is a sign. Our bodies need to be made new. Celebrating Christ’s victory, we wait for his return. On that day, caught up together with the saints in the clouds, Christ’s wounds will be the only blemishes we see. And we will not look away.

Lara Ryd is an editor for Perishable Goods. She lives in Michigan with her family.