Virtual Disorder and True Belonging

Why getting off Twitter and meeting your neighbor is good for you and everyone else

By Anna Timmis

In a Common Sense article titled “You’re Already Living in the Metaverse,” guest writer Antonio García Martínez claims that virtual media platforms, specifically Twitter and online news outlets, are real life, counter to what those who treat social media with skepticism state. He says that while he once believed that media activity was a weak reflection of reality, current events prove that “real life is increasingly a reflection of what happens online.” As an example, he states that comedian Dave Chapelle, after claiming that Twitter was not real life, went on to talk about a number of Twitter-related and curated topics, and then received a hit to his career via Twitter itself.

Perhaps he exaggerates the extent of Twitter’s influence, but I have personally observed and experienced the subtle but real-life harms of Twitter in my own life, and agree that we at least cannot dismiss the consequences of browsing or writing on Twitter (or other social media) throughout our day-to-day, whether professionally or recreationally. Twitter is toxic not because it doesn’t have a bearing on real life, but because it does.

We spend enough time on the Internet that it is itself a large part of life just by virtue of capturing our time and attention. A Baylor University study showed that college students spend between 8 and 10 hours on their cell phones per day. This was back in 2014, years before Covid lockdowns caused a spike in Internet activity. While college-aged students are just a fraction of the population, they will soon be our primary civic participants.

Twitter evidently has toxic effects on our happiness and even on our knowledge of current events. An MIT study titled “The Spread of True and False News Online” “found that falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.” Georgetown professor and author Cal Newport writes about meaningful work in a digital world in his book Deep Work. Newport, a professor of computer science, wrote in a recent blog post, “[Twitter] wasn’t intentionally designed to grasp our brain stem and squeeze it into an inflamed pulp of enraged emotions, but it turned out to be exceptionally good at accomplishing exactly this insidious goal.” Even thoughtful authors and theologians from whose books I have gleaned wisdom and encouragement in the Christian life show subpar judgment and grace in Twitter activity.

Twitter’s anonymity makes it ripe for conflict. The anonymity of the person on the receiving end of our comments makes it as easy to be uncharitable as our own anonymity. The comfort of anonymity doesn’t dissipate when a user publishes under her own name. That person becomes a sum of her political or theological leanings expressed via tweets, justifying petty and contentious exchanges. Additionally, our scarce knowledge from her profile flattens her out in our minds. Knowing a person’s name doesn’t mean knowing the person. We can’t see the look of hurt in the eyes or the flush of anger and shame in the face of the person we’re “talking to” on Twitter. We escape the natural consequences of conflict: navigating a strained relationship or even having to admit fault based on a reaction. We can pretend these consequences don’t exist because we often don’t have to experience them.

But just because we can’t see the damage we’ve done doesn’t mean it isn’t there. We ought to ask whether this popular use of time and mode of interaction supports fruitful community.

A good life does not mean avoiding civic issues; civic order and peace is crucial to flourishing. Assuming many use Twitter to have a grasp on major political or cultural topics and current events, its intended purpose is good. But the example of older, mature Christians has shown that efficacy—our ability to impact civic and cultural matters—starts with ordering priorities toward the people and things God puts in front of us.

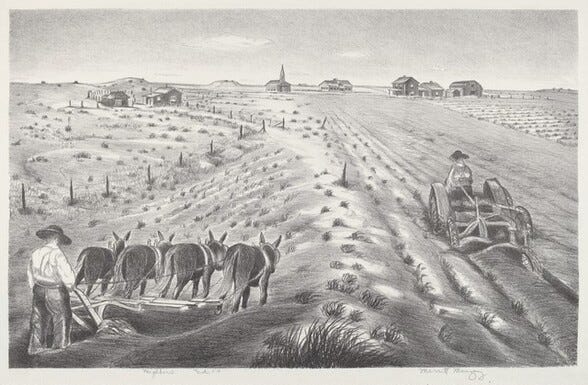

Growing up in a rural Michigan village, my neighborhood was made up of houses and farmsteads spotted over acres of wooded hills and fields. After winter storms, one local man would drive a snowplow around the neighborhood and clear the long driveways of his neighbors’ homes. I remember how the families would guard each other’s values, with parents talking to each other about occurences between the neighbor kids. One night, a man being chased by the police crashed his car on the road in front of my house and set off cross country. My brother’s friend stopped by to ask if he could borrow my dad’s four wheeler. He and others were out helping the police find the fugitive.

Far from suburban comforts and prior to the smartphone (and most people with too modest an income to have the newest technology) we didn’t have the luxury of ignoring one another. Different political and religious convictions existed, but my neighbors were not the sum of their political or religious leanings. Because we depended on each other, we knew each other, and in spite of all our differences, we loved through service and friendship.

Physical proximity was crucial to preserving these relationships because we were tempered by the physical and material consequences of disunity. If we caused conflict in our community, we couldn’t just walk away from our computers and phones and ignore it—we were sure to see that person in the grocery store or the library sometime that week. We felt the conflict in our bodies: the stress and exhaustion, the pit in the stomach. These sorts of physical ramifications can sometimes prove obstructions to daily life, like when you’re not able to do a good job as a teacher because of a conflict with a student’s parent. These may seem trivial examples, but they can destroy the sense of wellbeing and peace for which we long.

Considering how unpleasant disunity is, our healthy aversion to it motivates us to live with civility and forbearance. When we submit ourselves to these limitations of living in community, picking and choosing our battles, we hold together the fabric of civil society.

COVID-19 showed that when we retreat from proximity, we lose that tempering fear of the consequences. With the boundary lines down, our conflicts reached fever pitch. We each individually feel protected from the consequences of our lives on the Internet because we’re alone on the other side of the screen from everyone else.

The sum total of people’s words and actions, their kindness or the way they serve their families and keep their homes, changes how we understand and encounter opinions different from our own. As I grew up in my hometown, my mom remembers how some local family friends softened to Christianity, not because of airtight arguments from my parents, but because of countless shared meals and shared experiences such as their homesteading ventures or their kids’ community theater productions. In the same way, my mom came to understand why her friend’s political views were so different from her own. The conflicting ideology took on nuance in the living, breathing form of someone she could respect for her excellence in some area of her life. This friendship served as a small antidote to political and religious polarization.

While online national news helps us know and care about our country’s politics, only when we know our neighbors can we actually know enough about the interests of people to be responsibly politically engaged. It’s easy to fear that we won’t know what’s going on around us if we’re not engaging with social and virtual media. But focusing on your neighbors isn’t the same as burying your head under a rock and avoiding the pervasive problems in society. We can apply that knowledge of our neighbors to lend our voices in local politics in a way that serves them. Likewise, knowing local officials helps determine the quality of their character and their work regardless of party affiliation.

Martínez observes how elections give us something “real” to grasp in a world that is increasingly virtual. While virtual media often falsely conveys a homogeneity of American citizens or oversimplifies political divides (and even creates those divides, exemplified in the riots of last year and the year prior) the recent Virginia gubernatorial election showed that the media’s influence has its limits. It does not capture the diversity of individuals within local communities or the diversity of local communities from one another. For those who feel convicted about political involvement, participating locally builds the foundation for our political system to work well, ensuring that the local and state leaders influencing national leaders are accurate representatives.

Belonging to your community starts with ordinary friendly acts, though many of us have fallen out of practice in the past two years. You can start by having your neighbors for dinner, even if you don’t know them well. Take your extra coats down to the local shelter. Have those conversations about the big national topics to understand how they apply to your neighborhood. Talk to local business owners about economic struggles—sometimes there is something you can do. Go to church and stay afterward, braving even the most awkward of after-service conversations with the goal of fostering real friendships.

Ultimately, wielding influence does not come from thousands of retweets, but instead from patient and thoughtful local engagement. The delayed gratification of investing on the small scale and helping build a stronger foundation far outweighs the usefulness of Twitter. In the meantime, we’ll be happier and more content by working to make our small corners of the world better places, caring for and serving our neighbors.

Anna Timmis graduated from Hillsdale College and is pursuing an M.A. in journalism, PR, and new media at Baylor University.

1. Antonio García Martínez, “You’re Already Living in the Metaverse,” Common Sense.

2. Janice Wood, “College Students In Study Spend 8 to 10 Hours Daily on Cell Phone,” Psych

Central.

3. Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral S, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science.

4. Cal Newport “Analog January: The No Twitter Challenge” Study Break.